This article was first published in the CODART eZine, no.3 Summer 2013

With this special issue the Szépművészeti Múzeum’s is pleased to announce to all CODART members and supporters the opening of Rembrandt and the Dutch Golden Age in October 2014. Organized with the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm and the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, this exhibition has been a major undertaking that has been at least fifteen years in the making. It is the culmination of increasing promotion and growth of the museum’s significant holdings in Dutch, Flemish, and Netherlandish art, and more notably, demonstrates the Szépművészeti Múzeum’s ongoing commitment to that area of its collection.

2000 was an banner year for the museum because it coincided with the publication of the Summary Catalogue of the Early Netherlandish, Dutch and Flemish Paintings, , but for curators of Dutch and Flemish art, 2004 is perhaps more important. That year saw the completion of a newly renovated wing dedicated to seventeenth-century Dutch paintings. Installed under the guidance of Ildikó Ember, the display has enabled the museum to show 242 paintings, twice as many as previously. 25 themed guide booklets were produced to complement the reinstallation.

The museum’s renowned holdings in works on paper have also received significant attention in the past decade. Teréz Gerszi’s critical catalogue of the seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish drawings appeared in 2005. This long-awaited publication, which was the result of over a decade of research, contained a great number of previously unpublished works. It was accompanied by an exhibition of Rembrandt’s engravings and drawings commemorating the 400th anniversary of the artist’s birth. In Arte Venustas. Studies on Drawings in Honour of Teréz Gerszi, which came out in 2007 on the occasion of Gerszi’s 80th birthday, further celebrated the drawings collection and Gerszi’s tireless efforts. The drawings received additional exposure in the form of a loan exhibition of 70 sheets to the Louvre, La Renaissance aux Pays-Bas: dessins du Musée de Budapest (2008), organized by Gerszi and Carel van Tuyll van Serooskerken. Recently, the museum mounted The Age of Pieter Bruegel: Netherlandish Drawings from the 16th Century (2012), which was drawn mostly from the own collection with some important loans from abroad.

The museum’s collection continues to receive scholarly attention. In 2011 two critical catalogues, by Rudi Ekkart and Ildikó Ember, were published on the seventeenth and eighteenth-century Dutch and Flemish portraits and still lifes. Last year saw the publication of Geest en gratie. Essays presented to Ildikó Ember on Her Seventieth Birthday. Many of the 29 contributions, authored mostly by CODART members, naturally focus on pieces from the Budapest collection. For 2013 we anticipate seeing in print Zsuzsa Urbach’s critical catalogue of the museum’s early Netherlandish paintings.

New Acquisitions and Paintings on Long-Term Loan in the Szépművészeti Múzeum

The museum’s centenary celebrations in 2006 were marked not only by important exhibitions, jubilee events and the publication of a large special edition album, but also by a memorable acquisition: The Agony in the Garden from Bernard van Orley’s four-part Passion series (fig. 1). The other three from the series are in the United Kingdom and Germany: Crowning of Thorns (Hannover), Christ Carrying the Cross (Oxford), and Preparation for the Crucifixion (Edinburgh). The series is documented in an inventory from 1535, compiled when Henry III of Nassau and his wife Mencía Mendoza moved from Spain to Breda. According to the inventory, the rectos of Orley’s pictures were decorated with the owners’ coats of arms and transported in separate crates. Those on the back of the Budapest picture are the best preserved.

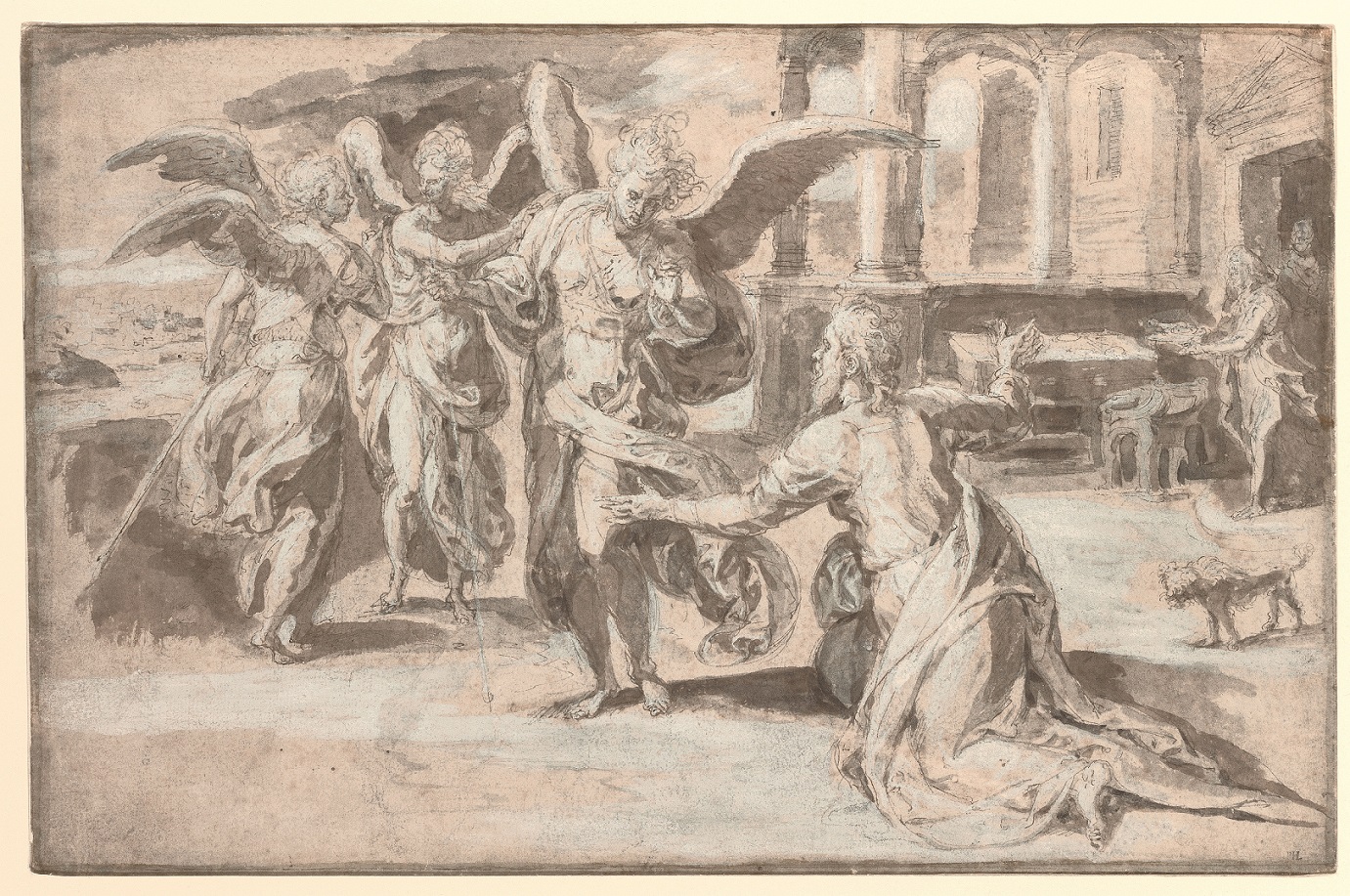

Fig. 2. Chrispijn van den Broeck (1524-1590), Abraham and the Three Angels, 1580

Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest

Through purchases, gifts, and long-term loan arrangements, the museum has been fortunate to add significant examples of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Antwerp masters and workshops, bolstering the museum’s holdings in Netherlandish and Flemish art. The earliest of them is the small-scale tondo of St Christopher Carrying the Christ Child from the circle of Joachim Patinir. Also notable is a drawing by Chrispijn van den Broeck’s of Abraham and the Three Angels from 1580 (fig. 2). Van den Broeck worked for many years in Frans Floris’s workshop, and in this mature work, the dynamic, slender and elegant figures are closest to the drawings of archangels by Maarten de Vos and the engravings made after them.

We also acquired two paintings from the workshop of Jacob de Backer. One of them, The Allegory of Smell, is from a series of five senses, for which the museum already had a piece , that of Sight. Two others, Touch and Taste, remain in a Hungarian private collection. On long-term loan is a large-scale Last Judgement, a splendid example of the painter’s decorative, Mannerist palette (fig. 3). Backer’s Five Senses and Last Judgement enjoyed great popularity in the period around 1600, as evidenced by the many variants and replicas. Another long-term loan is Abraham Janssens’s Allegory of Joy and Melancholy. (fig. 4). Three versions of the composition are known, including one that was once in the Brussels collection of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria.

-

Fig. 3. Jacob de Backer (1540-1591) , Last Judgement

Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest

-

Fig. 4. Abraham Janssens (1567-1632), Allegory of Joy and Melancholy

Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest

A major coup was the acquisition of the Catafalque of Archduke Albert. The picture was on the list of the museum’s war losses until it was re-discovered in a Hungarian private collection over 60 years later, when the museum had the opportunity to repurchase it. The signature, which cannot be read with certainty, has led to a tentative attribution to the engraver Karel van Mallery. In the nineteenth century it was known to be in the same collection as its pendant, The Catafalque of Infanta Isabella.

Fig. 5. Willem de Poorter (1608-1649/68), Allegory of Colonial Power, 1638

Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest

Important examples of seventeenth-century Dutch painting have also recently entered the collection, including a previously unknown work by Willem de Poorter called Allegory of Colonial Power. (fig. 5). Dated to 1638, the painting’s unusual iconography is certainly linked to contemporary historical events. In the summer of 1637 the Dutch occupied the West African fortress Elmina (São Jorge da Mina), which had formerly been under Portuguese rule, and thus a new European power took control in the Gold Coast. The sovereign in De Poorter’s painting is the personification of the United Provinces, to whom the indigenous inhabitants of the newly colonized regions bring valuable gifts as a token of their homage. The painting is on long-term loan from a Hungarian private collection.

Pieter Quast’s tronie of A Man Writing also comes from an important Hungarian private collection that dates to the end of the nineteenth century. Purchased by the museum in 2007, the painting depicts neither high society, peasants nor the life of soldiers, yet the painter’s humour and fondness of caricature is undeniably apparent.

A milestone for the museum was the 2004 purchase of Barent Fabritius’s Sacrifice of Manoah. For almost a century after it last surfaced in 1911 in Budapest, after the Berlin auction of the Hungarian Gerhardt Collection, the whereabouts of the painting remained unknown. In contrast to most seventeenth-century depictions of the theme, the figure of the angel is missing from Fabritius’s work; it was already absent at the time of the 1911 auction. Technical examination of the picture now in Budapest has confirmed that the upper part of the panel with the angel was trimmed at the end of the nineteenth century. The whereabouts of the panel with the angel are still unknown.

Fig. 6. Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen (1593-1661), Portrait of a Woman, 1651

Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest

More recently in 2008 the museum acquired Johnson van Ceulen’s Portrait of a Woman (1651), which was once in the collection of Maurice Kann. (fig. 6). Along with its pendant (whereabouts unknown), which was executed nine years later, the paintings are rare examples of the artist’s later works in which he depicted his models seated.

About the author: Júlia Tátrai

Júlia Tátrai graduated from Eötvös Loránd University in art history and Netherlandic studies. Since 1997 she has worked at the Szépművészeti Múzeum, where she is the curator of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish paintings. She has published and lectured widely on Netherlandish art. Her studies deal with questions of attribution (Jacob de Backer invenit – The Allegory of Smell), iconography (The Return of Barent Fabritius’s Sacrifice of Manoah to Hungary), and the history of collecting (Eine “andere” Esterházy-Sammlung. Die Gemälde des ehemaligen Plettenberg-Esterházy Schlosses in Nordkirchen). In 2010 she was the first recipient of the Hungarian Isabel and Alfred Bader art historian research stipend. She is the co-curator of Rembrandt and the Dutch Golden Age, which is scheduled to open at the Szépművészeti Múzeum in 2014.

Júlia Tátrai is Curator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, Hungary. She has been a member of CODART since 2003.