This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no.4 Summer 2014.

Paul Knolle studied art history at Utrecht University and was affiliated with the department of art history as a researcher and teacher. Since 1997 he has been Head of Collections and Curator of Fine Arts at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede, for which he has organized various exhibitions on eighteenth-century art. He has published on such subjects as art education, satirical prints and eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century art theory. He is currently working on a dissertation on the origin of Dutch drawing academies in the eighteenth century.

For this eZine devoted to eighteenth-century art and art-collecting, Paul Knolle was interviewed by Andrea Rousová, Curator of Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Dutch Art at “Národní galerie v Praze.”

I will start with a question to which I’m not expecting a scholarly answer: What is your favorite piece of art from the collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe and why?

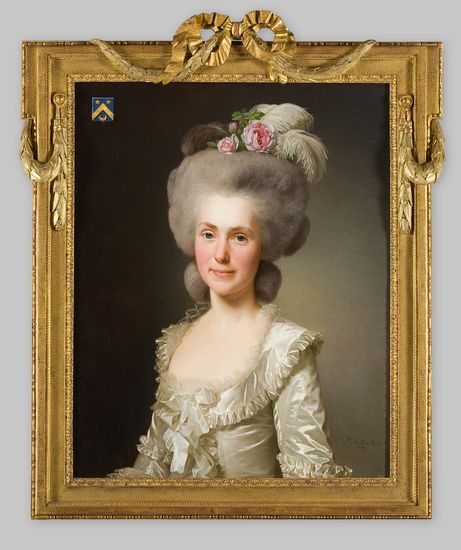

It is almost impossible to make a choice from the Rijksmuseum Twenthe’s broad collection. Joos van Cleve’s subtle portraits of a man and his wife? Or the landscape by Thomas Gainsborough, one of my favorite painters, whose small painting we bought in 2010? Or the intimate landscape of 1862 by Andreas Achenbach? But by all means let me choose. Actually, I have two favorite paintings which, being pendants, belong together. They are the portraits of the French couple Maria Romain Hamelin and Marie Jeanne Puissant, painted in 1781 by the Swedish artist Alexander Roslin (1718-1793). Not only are these paintings beautiful in the facial expressions and the representation of the clothes, but they are also characteristic of my favorite period in the history of art: the long eighteenth century. I still think it very special, how the portraits were acquired by the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in 2008.

- Attributed to Joos van Cleve (1585-1540), Portrait of an Unknown Man, ca. 1515, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, inv. no. 0027 (photograph R. Klein Gotink)

- Attributed to Joos van Cleve (1485-1540), Portrait of an Unknown Woman, ca. 1515, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, inv. no. 0028 (photograph R. Klein Gotink)

As usual, the director of the museum (in those days Lisette Pelsers) and I visited The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF) in Maastricht. After a few hours we met and exchanged experiences. Lisette said that she hadn’t seen any artworks that would fit logically in our museum’s collection, apart from two portraits by “a certain Ros … Ros… .” I immediately knew who and what she meant. I had seen Roslin’s portraits at Åmell’s stand. Roslin was already one of my favorite artists. Just at this time, a large Roslin exhibition was taking place in Versailles. When visiting Stockholm, I had seen several of his masterpieces in the Nationalmuseum. Fortunately, the Rembrandt Association and the Mondriaan Foundation agreed with us and gave the museum financial support.

Alexander Roslin (1718-1793), Marie Jeanne Puissant (1745-1828), 1781, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, inv. no. 4250 (photograph R. Klein Gotink)

That was not all. When I mentioned the purchase of the Roslins to Karin Sidén, then Chief Curator and Director of Research at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, she told me that the Nationalmuseum would be closing for a long period of renovation. This conversation, which took place during a CODART dinner, resulted in the idea of mounting a Roslin exhibition at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe. The exhibition will open in October 2014 and includes no fewer than sixteen masterpieces from the Nationalmuseum. At last the Dutch public will have an opportunity to become acquainted with Roslin’s wonderful works. It is a great pleasure to be able to tell you all of this!

Please tell us about your professional career after your university studies.

After studying art history in Utrecht, my first real job was at the Centraal Museum in the same city. There, in 1978-79, I helped prepare the exhibition De kogel door de kerk (or The die is cast), to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the signing of the Union of Utrecht. Immediately after that, I started working at Utrecht University, teaching and doing research. After about ten years, I left the university and began working freelance. In the meantime, I had moved to Enschede, in the eastern part of the Netherlands. When I heard that the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in my new home town was planning to pay more attention to the art and culture of the eighteenth century, I approached the director, Dorothee Cannegieter. The museum decided to focus on this period when it became independent in the mid-1990s. Other Dutch museums paid almost no attention to art from the period 1680-1820. Dorothee invited me to help prepare the exhibition Feesten in de 18de eeuw (Festivities in the 18th century). In 1997, I was asked to become the Head of Collections and Curator of Fine Arts, and here we are now, seventeen years later.

Since 1997 the Rijksmuseum Twenthe has considerably enhanced its collection of eighteenth-century art through acquisitions and loans. In fact, we have regularly shown eighteenth-century art in the permanent display and organized many exhibitions on this period, from monographic presentations on artists such as Cornelis Troost, Tibout Regters, Abraham and Jacob van Strij, Wouter Johannes van Troostwijk and Nicolaas Verkolje to presentations on architecture, satirical cartoons, and ceramics from this period. A highlight was the exhibition The Year of the 18th Century, held in 2007, when more than 130 paintings were exhibited from the museum’s collection, as well as from the collections of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, the Frans Hals Museum and the Dordrechts Museum. Now that our public has had ample time to become acquainted with eighteenth-century art, we have decided that art of the eighteenth century is an integral part of the museum’s presentation of art throughout the centuries. I have a broad interest in eighteenth-century art and culture in general. I have published on art education (and am still finishing my PhD dissertation on the rise of art academies in the Netherlands in the eighteenth century), satirical prints, birds in art, and artists of the eighteenth century.

Your name is mainly connected with the eighteenth century. Was it your own choice, or did you just feel that there is a lack of research on that period, compared to the research done on the Golden Age? Or were you prompted to specialize in this period by the great collection of Dutch classicism in Twenthe?

My interest in eighteenth-century culture was encouraged by one of my teachers at Utrecht University, Johannes Offerhaus. The more I looked at eighteenth-century paintings and read primary and secondary sources from that period, the more my interest grew. The eighteenth century was in many ways extremely modern – not only art-historically speaking – and in the Netherlands almost no research was being done on that period, because artists and themes from the Golden Age were much ‘sexier’ and more prestigious. There was so much to do, so much to be studied, that an enormous field of interest opened up. It felt like pioneering work. And even now, decades later, there is still so much to be done! I was reluctant to confine myself to researching and writing about eighteenth-century subjects, but I was quite happy to get the opportunity, thanks to my work in the museum in Twenthe, to show the Dutch public art and artists that were ‘new’ to them. The period when we could show not only our own art from 1680 to 1820, but also the most important works from that period on loan from the Rijksmuseum really made me happy. So my interest in the eighteenth century was there rather early, the museum came later.

The first retrospective exhibition of Nicolaas Verkolje – Nicolaas Verkolje (1643-1746). The Velvet Touch – was held at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in 2011 and you were part of the research team. Thinking of the conceptual framework of the exhibition, did you aim to show Verkolje primarily as a technically brilliant painter, or did you want to demonstrate other of his qualities?

Nicolaas Verkolje (1673-1746), Moses Found by Pharaoh’s Daughter, 1740, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, inv. no. 1606 (photograph R. Klein Gotink)

The Verkolje exhibition was inspired by our admiration of his technical skills and the attractiveness of his paintings. Here was an intriguing, wonderful artist, completely unknown to the public, with no monograph written about him – and the museum owns one of his masterpieces, The Finding of Moses. Once we had begun our research, Verkolje’s work proved interesting in many ways. To begin with, he worked with French engravings and etchings when composing his paintings. He was not only a great painter, but also a brilliant mezzotint maker. An exhibition like this one, in which three versions of The Finding of Moses could be compared, was a voyage of discovery for art historians and art lovers alike. It was a joy to work with nine colleagues – all with different levels of experience – on the exhibition and the catalogue.

Would you please tell us about a few eighteenth-century artworks in your museum that have interesting or remarkable provenances?

Willem Joseph Laquy (1738-1798), The Waffle House, 1775, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, inv. no. 4116 (photograph R. Klein Gotink)

Let me choose one interesting example: Willem Joseph Laquy’s painting Het Wafelhuis (The Waffle House) of 1775, which we bought in 2006. Laquy, who lived from 1738 to 1798, is an interesting and attractive painter who deserves an exhibition. He was born in Brühl, between Cologne and Bonn, and came as a young artist to work in Haarlem. The Waffle House is a good example of his genre paintings and of the trend in Dutch painting from the mid-eighteenth century onwards to look to seventeenth-century art for inspiration. The painting comes from a private collection in Belgium, but we also know a little bit more about it. Research has shown that the painting originally belonged to the collection of Jan Gildemeester, one of the most important eighteenth-century Dutch collectors. Gildemeester and another well-known collector, Gerrit Braamcamp, were enthusiastic about Laquy’s work and became his patron. The painting in the Rijksmuseum Twenthe is described in glowing terms in the second part of Van Eynden and Van der Willigen’s Geschiedenis der vaderlandsche schilderkunst, sedert de helft der XVIII eeuw, published in 1817. And then there’s another painting: Willem van Mieris’s Diana with Nymphs of 1702 has an impeccable provenance, going back to the early eighteenth century. One of the owners was the art collector Jonas Witsen, an Amsterdam politician who had a kunstkamer and a collection of curiosities.

The collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe contains art and applied art from the thirteenth century to the present. In the event of an exhibition, you have material to work with from at least nine periods. Could you tell us more about the “dramaturgy” of the exhibitions planned by the Rijksmuseum Twenthe for the coming years?

The collection is very broad indeed, so we can choose from many different subjects. The themes of the exhibitions planned for the next few years vary from Southern Netherlandish art in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp (a ‘triptych’ that includes Flemish expressionists, Baroque art, and fifteenth- and sixteenth-century art) to early work by one of the greatest living artists, Jan Fabre, also from Belgium.

There will be two exhibitions of art from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the first devoted to the above-mentioned Alexander Roslin and the other to Turner (2015). The Turner show, organized in cooperation with the Museum de Fundatie in Zwolle, will be absolutely spectacular. In fact, we strive to make all of our exhibitions exciting in one way or another. If visitors are indifferent to what they see, we are disappointed. For example, in the Roslin exhibition, we tell the story of each person Roslin painted. A beautiful portrait may be in stark contrast to the sitter’s story. Some of the heads he portrayed fell under the guillotine. The presentation shows Roslin at his best, but also provides insight into political and socio-economic developments in the second half of the eighteenth century. Our aim, after all, is to show art in a broader context.

Are you preparing any project in particular – an exhibition, study or article – that focuses on the history of collecting in the eighteenth century?

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Wooded Landscape with a Shepherd Resting by a Sunlit Track and Scattered Sheep, ca. 1745-1746, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, inv. no. 4475. Acquired with the assistance of the Rembrandt Association (photograph R. Klein Gotink)

It depends on what you call a concrete project. For example, the museum is preparing, together with the Dordrechts Museum, an exhibition on Aart Schouman, the multi-talented eighteenth-century Dutch artist. In Enschede we are going to show many of his wonderful watercolors of birds and mammals, which he studied in many cabinets of curiosities in the Netherlands. Schouman was in touch with some very important collectors of European and exotic birds. He was an artist turned scientist, or vice versa – a process that interests me very much. I also hope to organize an exhibition of portraits of eighteenth-century collectors from many countries, including the Netherlands, Great Britain, France, Germany and Scandinavia – an extremely intriguing subject.

You already mentioned the role of CODART in the upcoming Roslin exhibition. What does CODART mean to the realization of exhibitions at your museum?

CODART remains very important in this respect. For example, when Karen Hearn told me at a CODART congress about the upcoming renovation at Tate Britain and the fact that fewer works could be shown during that period, we immediately discussed the possibility of presenting some eighteenth-century British portraits at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe. In the end, we received no fewer than twelve portraits from the Tate – by William Hogarth, Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, George Romney, Thomas Lawrence and other artists – for the 2012 exhibition Ladies and Gentlemen. Portraits from the British Golden Age. The cooperation with the Tate will continue: the Tate will be the main lender for the wonderful Turner exhibition which the Rijksmuseum Twenthe and the Museum de Fundatie will mount in the autumn of 2015. Moreover, the three incredible exhibitions taking place in 2013-2015, with works from the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, would have been inconceivable without the contacts made at CODART activities. Clearly, we are extremely grateful to Paul Huvenne and his staff in Antwerp. CODART therefore plays an important role in the development of exhibition projects at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe by creating a climate of inspiration and cooperation.

Paul Knolle is Head of Collections and Curator of Fine Arts at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede, The Netherlands. He has been a member of CODART since 2000.

Andrea Rousová is Curator of Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Dutch Art at the Národní galerie v Praze in Prague, Czech Republic. She has been a member of CODART since 2012.