This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 7 December 2015.

‘To paint or to draw always meant to him to invent’, wrote Max J. Friedländer, the great connoisseur of early Netherlandish painting, about Jheronimus Bosch (c. 1450-1516).2 He was praising Bosch’s unorthodoxy, his originality. In the past few years the Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP) has been carrying out intensive research on Bosch’s work, with a special emphasis on the genesis of his paintings. Partly with the aid of systematic infrared photography and reflectography and standardized macrophotography it has been demonstrated that Bosch was indeed the ‘molding inventor’ that Friedländer saw in him. He was a tinkerer, a painter who thinks on the panel, coming up with new ideas and implementing them during the working process. With Bosch there is often a lot going on beneath the painted surface.

Modern imaging techniques have expanded the range of the connoisseur’s research apparatus, with the result that the group of paintings that Friedländer attributed to Bosch in 1927 (and in the English edition of 1969) has been drastically modified (and reduced). All the science and technology, though, does not alter the fact that it can be said without reservation that connoisseurship has played a part in every single attribution to Bosch as matters stand today.

None of the known works by Bosch can securely be traced back to his workshop. The world of archival records (of which there are quite a few relating to Bosch) and that of his paintings are largely separate. Connoisseurship in Bosch studies is therefore vitally important. That also means that we are always on thin ice when speaking of Bosch, for connoisseurship is based on the connoisseur’s eye combined with his ability to communicate what he sees. So it is more a question of a gut feeling than hard science.

Dendrochronology has proved to be a valuable player in the attribution game, and in several cases it has corrected a connoisseur’s mistaken eye. However, dendrochronology can only reject paintings, and then only if they are on oak or another wood for which there are chronologies. Examples in the Bosch oeuvre are The Marriage at Cana (Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen) and The Crowning with Thorns (Patrimonio Nacional).3

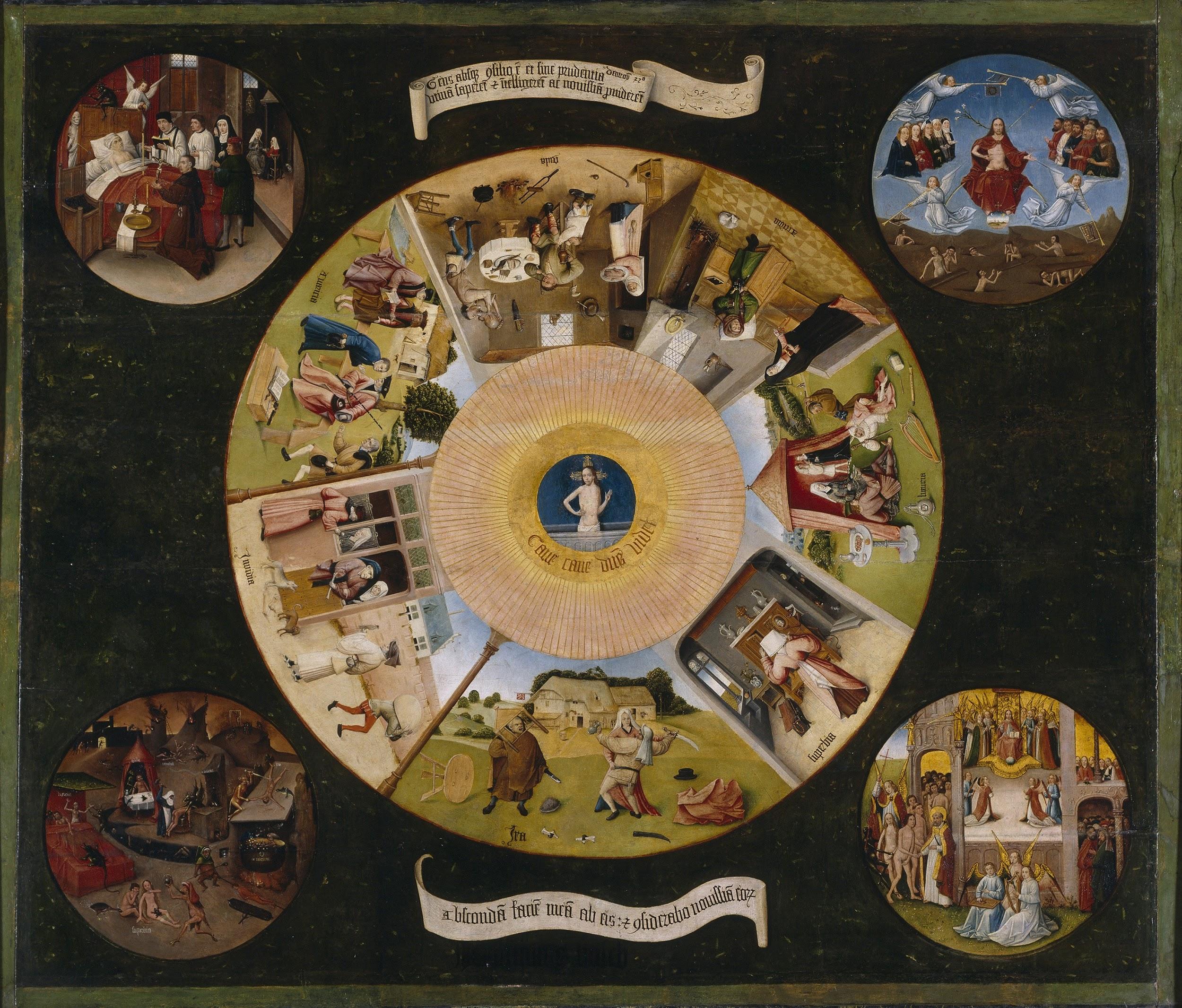

Jheronimus Bosch (1440/1460-1516), The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, ca. 1500, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

In the case of The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, which is on poplar, no ‘easy’ judgment can be arrived at by counting annual rings.4 The painting, which is signed ‘Jheronimus bosch’, shows man’s sinful behavior reflected in the eye of the Lord. And written in the iris of that eye is the saying ‘Cave cave dominus videt’, ‘Beware, beware, the Lord sees’. Conceptually the scene fits perfectly within the cultural context of the city of ’s-Hertogenbosch.5 On top of that, the picture has a royal provenance, for it is said that it was in the very room in the Escorial where Philip II breathed his last on 13 September 1598.6 So it also fits perfectly in a story about Philip’s devotion. In this case the provenance makes the painting more important, and in its turn the painting makes the owner’s devotion all the stronger.

Jheronimus Bosch (1440/1460-1516), Death and the Miser, ca. 1500-1510, Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington-

Around 1560 the Spanish humanist Felipe de Guevara described the painting in a famous passage of his Comentarios de la pintura. ‘However, it is only fair to report that among those imitators of Hieronymus Bosch there is one who was his pupil and who, either out of reverence for his master or in order to increase the value of his own works, signed them with the name of Bosch rather than his own. In spite of this fact his paintings are very praiseworthy, and whoever owns them ought to esteem them highly; for in his allegorical and moralizing subjects he followed the spirit of his master, and in their execution he was even more meticulous and patient than Bosch and did not deviate from the lively and fresh qualities and the coloring of his teacher. An example of this kind of painting is a table in the possession of Your Majesty, on which are painted in a circle the Seven Capital Sins in figures and examples; and while this is admirable in its entirety, it is especially the allegory of Envy which in my opinion is so excellent and ingenious and in its meaning so well expressed that it can vie with the works of Aristides, the inventor of such paintings which the Greeks call Ethike – meaning in our tongue as much as pictures which have as their subject the habits and passions of the soul of man.’7 The way in which this passage is phrased has suggested to some that De Guevara is describing the picture as an example of the work of a Bosch pupil who signed it Jheronimus Bosch out of respect and reverence for his master. However, there is a difference of opinion about the precise interpretation of the passage, which is also cited as an argument for an attribution to the master himself.

If connoisseurs had no doubt about its authorship, this picture would definitely be one of the benchmarks in the oeuvre. However, many experts believe that it is not by Bosch,8 and the BRCP agrees.

It is a pity, then, that this painting cannot yet be included in the program of the BRCP, which has been endeavouring since 2010 to document all the paintings attributed to Bosch with macrophotography in visible light and the infrared, among other aids. It would be very interesting to learn more, and in greater detail, about the similarities and differences in the rendering of the figures of Death, for instance, in the so-called Tabletop and The Death of the Miser in Washington, for comparisons of that kind lend greater weight to discussions about attributions.

- Jheronimus Bosch (1440/1460-1516), Death and the Miser (detail), ca. 1500-1510, Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington-

- Detail of Death in The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (Museo Nacional del Prado)

For the time being, the rather awkward handling of the figures in The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (however charming they may be) suggests that this is a product of Bosch’s shop or the work of a follower. At present it is hard to detect Bosch’s hand in it, that is to say a hand that is demonstrably, in the sense of visibly, comparable to that in other paintings that are attributed to him.

Jheronimus Bosch (1440/1460-1516), The Garden of Earthly Delights, ca. 1500-1515, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

That is different, for example, with a work like The Garden of Earthly Delights and the drawing of The Tree Man in the Prado and the Albertina respectively. Google collaborated with the Prado to make a very high resolution photograph of The Garden of Earthly Delights, which it put on line through Google Earth. That makes it possible to zoom in so close that painter’s hand becomes visible. The same can now be done with the Vienna drawing through the BRCP documentation. Although it is a work of art in the different medium of pen and ink on paper, as against oil paint on panel, and on a different scale (the drawn tree man is roughly 13 cm high, whereas his counterpart in the painted detail is 62 cm high), the way in which both are made is very similar. A connoisseur would see the same hand in both.

Comparison of a tree man in The Garden of Earthly Delights (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid) and Tree Man (Albertina, Vienna)

These and many other comparisons can be made with the online digital infrastructure that the BRCP is building with support from The Getty Foundation and other bodies, which will go live in early 2016.9 Connoisseurship can only flourish where comparisons can be made. The larger the number of possible comparisons the larger the number of potential arguments that can be advanced on the basis of those comparisons.

Giovanni Morelli, the famous nineteenth-century connoisseur, illustrated his arguments for distinguishing between hands with outline drawings of the way different artists painted details like ears. The criticism of his method notwithstanding, his idea of gaining a keener insight through comparison is still valuable.

- Comparison of ears by Giovanni Morelli (1816-1891)

- Comparison of ears in Christ carrying the Cross (Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent) (top left and right), Saint Christopher (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam) (bottom left) and Saint Jerome in Prayer (Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent) (bottom right)

If we now imitate Morelli and put a number of ears from paintings in the Bosch group side by side, one immediately spots the differences and similarities. It is a small but illuminating illustration of the value of high-quality, standardized photography and macrophotography for the study of paintings, for it enables comparisons to be made on a level that cannot be achieved with a single-shot photograph.

Jheronimus Bosch (1440/1460-1516), Infernal Landscape , pen and brown ink on paper, private collection

This becomes all the clearer if one examines a drawing in a private collection. The sheet, a Hell Landscape, was auctioned in 2003 and has never yet been seen in public.10 The BRCP was allowed to examine the drawing so as to document it in the standardized way that the project applies to the rest of Bosch’s oeuvre. The drawing was first published at length by Fritz Koreny in his catalogue of the drawings,11 and according to him it is a drawing by an assistant of the Master of the Bruges Last Judgment. He suspects that it was drawn around 1520, that is to say after Bosch’s death. The attribution of the sheet to an artist working at a later date after Boschian models follows from Koreny’s conviction that the drawing is in the nature of a pastiche. Elements in it recur in paintings, drawings and underdrawings of the Bosch group, and according to him that is precisely where they were taken from. In other words, they were not prepared by the master himself on this sketchbook sheet or developed any further.

That the latter can be done is evident from the above comparison between The Garden of Earthly Delights and The Tree Man. The drawing cannot be regarded as a preliminary study for the detail in the painting. It is too autonomous for that. Whether it was made before or after the picture is impossible to say for certain. The most logical idea, perhaps, is that it is an autonomized rendering of one of Bosch’s most successful inventions, in other words a drawing made at a later date and in the presence of the painting.

The Hell Landscape is sketchier than The Tree Man. It is not so much a reworked and finished composition but more an assemblage of scenes and forms that recall hell. In our view it testifies far more to a searching draftsman than to a copying one. In a detail at lower left, a group of unfortunates are lying and sitting on the blade of a knife. A copyist would have interrupted the outline of the blade at the positions occupied by the figures. The same applies to the odd figure seated on the bipedal barrel at bottom right, with the outline of the barrel continuing through the hindquarters of the helmeted birdman monster.

- Detail of Infernal Landscape (private collection)

- Detail of Infernal Landscape (private collection)

The way the draftsman renders the arrow in the monster’s beak is almost identical to the way the draftsman of a monster does in a drawing in Berlin. The same applies to the manner of hatching the leg sticking out of the barrel, compared once again to the Berlin monster. The strange way in which the toes of the seated monster are attached to its left foot matches the depiction of the foot of one of the two old women in a drawing in Rotterdam. In our view, these similar details betray the hand of an inventor draftsman and not of a copyist.

- Detail of Two Monsters, Pen and brown ink on paper, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Comparison of small figures in the Infernal Landscape (private collection) and The Garden of Earthly Delights (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

Comparisons between drawings and paintings are also valid in this case. Compare the depiction of one of the birds perched on a pole at top right in the drawing with the way a small bird was painted on one of the outer wings of Bosch’s Temptation of St Anthony Triptych in Lisbon. Several comparisons with The Garden of Earthly Delights are also possible. Once again it is a matter of details like Morelli’s ears and the odd way those details have been given shape by the painter-draftsman’s use of pen and brush. The peculiarly long arms and hands of the figures in the background of the right wing of the Garden are very similar to those in the drawing. These and other comparisons make it clear that the Hell Landscape drawing must be attributed to Bosch and not to a copyist.

But not everyone will be won over by this attribution to Bosch. What the Bosch Research and Conservation Project is going to offer, in addition to the conventional printed publications, is a very extensive and highly advanced digital infrastructure with which the above comparisons can very simply be checked, modified and above all supplemented. This represents a major advance in the study of Bosch’s art. What is so elegant about this infrastructure is that no part of it is specific to Bosch. That makes the BRCP a project that deserves to be imitated. And it is here that good, consistent, standardized macrophotography comes into its own.

Matthijs Ilsink is Curator Jheronimus Bosch Research at the Noordbrabants Museum. He has been an associate member of CODART since 2010.

Notes

[1] The author is coordinator of the Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP) and joint curator of the exhibition Jheronimus Bosch – Visions of Genius, which will be on show in Het Noordbrabants Museum in ‘s-Hertogenbosch from 13 February to 8 May 2016. The BRCP research is a team project, the other members of which are Jos Koldeweij, Ron Spronk, Luuk Hoogstede, Robert G. Erdmann, Rik Klein Gotink, Hanneke Nap and Daan Veldhuizen. The ideas put forward in this article are presented in amplified form in Matthijs Ilsink, Jos Koldeweij, Ron Spronk, Luuk Hoogstede, Robert G. Erdmann, Rik Klein Gotink, Hanneke Nap and Daan Veldhuizen, Jheronimus Bosch, Painter and Draughtsman. Catalogue Raisonné, Brussels (Mercatorfonds) 2016.

[2] Friedländer 1969, p. 67.

[3] Klein 2001, pp. 129, 128 respectively.

[4] Garrido and Van Schoute 2001, pp. 77-95.

[5] Dionysius Carthusianus was made prior of the Sinte Sophie monastery in ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1466. His Speculum conversionis peccatorum (Mirror of the Conversion of Sinners), and even more so his edition of Cordiale quattuor novissimorum (English translation: Cordyal of the Four Last and Final Things, Westminster [William Caxton] 1479) are important sources for the painting. Both can be cited in support of the thesis that it was painted by someone in Bosch’s circle.

[6] Ponz 1788, pp. 41-44.

[7] Wolfgang Stechow, Northern Renaissance Art 1400-1600: Sources and Documents, Evanston 1999, p. 20.

[8] See Koreny 2012, p. 110.

[9] The website is being designed and built for the BRCP by Robert G. Erdmann. The address is boschproject.org, which is currently hosting a pilot version to demonstrate, among other things, the viewers that Erdmann developed for the BRCP.

[10] Sotheby’s, New York, Old Master Drawings, 21 January 2003, lot 20.

[11] Koreny 2012, no. 13, pp. 218-220.